Miscellany #5 Universe, Poems of Walt Whitman & Robert Frost

We are an impossibility in an impossible universe. - Ray Bradbury

From the Editor

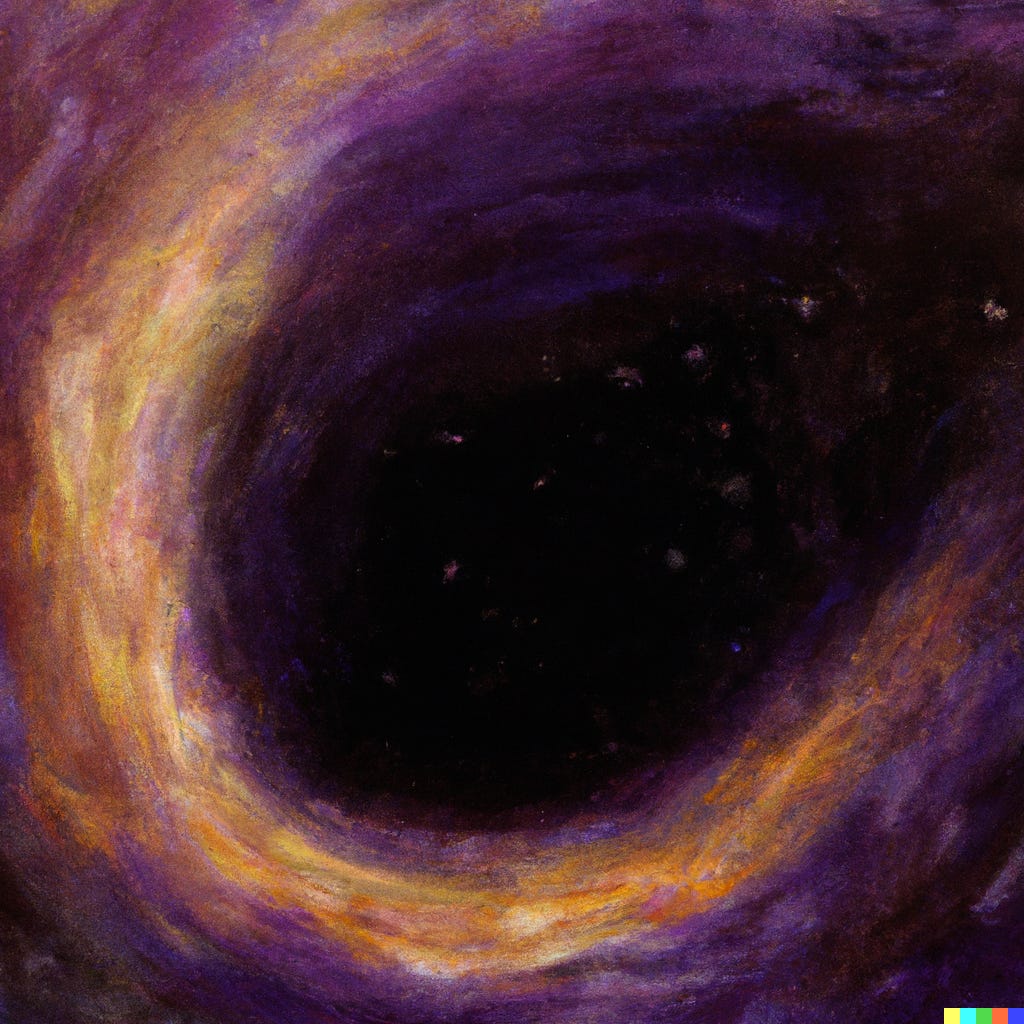

The poem reflects on the concept of singularity, the moment in time when the universe emerged from a single point of infinite density. It contemplates what came before this moment and how everything in the universe can be traced back to this single element. The poem highlights the similarities between science and poetry in understanding the universe's mysteries and how singularity has connected everyone and everything. The poet encourages readers to ponder the mystery of singularity to find answers to the questions that puzzle us.

Singularity

Singularity, the birth of time, From infinite density, the universe did climb, But what came before this grand design? What existed before this point, divine?

As I travel and read, patterns emerge, In magic and writing, beauty does converge, Science and poetry, are two lenses to view, The universe's secrets, we can pursue.

Everything traces back to that single point, A logistic map, connections we anoint, The singularity, a link between us all, The beginning of everything, big and small.

Let us ponder this grand mystery, The singularity's power, and history, For in its secrets, we may find, The answers to questions that haunt our minds.

“When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer” by Walt Whitman

"When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer" is a poem by Walt Whitman that critiques the idea that science and rational analysis can fully explain the beauty and wonder of the universe. The poem describes the speaker attending a lecture by an expert astronomer, who presents mathematical calculations and scientific observations to describe the stars and planets. The speaker becomes bored and restless, longing to experience the universe in a more visceral and intuitive way. He leaves the lecture hall and goes outside, where he gazes up at the stars and experiences a sense of awe and wonder. The poem suggests that while science can provide valuable insights into the workings of the universe, it cannot capture the full range of human experience and emotion that comes from direct engagement with the natural world.

When I heard the learn’d astronomer,

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me,

When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them,

When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

“The Star-splitter” by Robert Frost

"The Star-Splitter" by Robert Frost tells the story of a man named Ezra who is fascinated with the stars and spends his nights gazing at them through a telescope. Despite ridicule from his neighbors and even his wife, Ezra persists in his pursuit of the stars, believing that there is something important to be learned from them. The poem reflects on the tension between scientific inquiry and social convention, as well as the human desire to explore the mysteries of the universe. Ultimately, the poem suggests that Ezra's passion for the stars is a worthy pursuit, even if it is misunderstood or unappreciated by others.

You know Orion always comes up sideways.

Throwing a leg up over our fence of mountains,

And rising on his hands, he looks in on me

Busy outdoors by lantern-light with something

I should have done by daylight, and indeed,

After the ground is frozen, I should have done

Before it froze, and a gust flings a handful

Of waste leaves at my smoky lantern chimney

To make fun of my way of doing things,

Or else fun of Orion's having caught me.

Has a man, I should like to ask, no rights

These forces are obliged to pay respect to?"

So Brad McLaughlin mingled reckless talk

Of heavenly stars with hugger-mugger farming,

Till having failed at hugger-mugger farming,

He burned his house down for the fire insurance

And spent the proceeds on a telescope

To satisfy a lifelong curiosity

About our place among the infinities.

"What do you want with one of those blame things?"

I asked him well beforehand. "Don't you get one!"

"Don't call it blamed; there isn't anything

More blameless in the sense of being less

A weapon in our human fight," he said.

"I'll have one if I sell my farm to buy it."

There where he moved the rocks to plow the ground

And plowed between the rocks he couldn't move,

Few farms changed hands; so rather than spend years

Trying to sell his farm and then not selling,

He burned his house down for the fire insurance

And bought the telescope with what it came to.

He had been heard to say by several:

"The best thing that we're put here for's to see;

The strongest thing that's given us to see with's

A telescope. Someone in every town

Seems to me owes it to the town to keep one.

In Littleton it may as well be me."

After such loose talk it was no surprise

When he did what he did and burned his house down.

Mean laughter went about the town that day

To let him know we weren't the least imposed on,

And he could wait—we'd see to him tomorrow.

But the first thing next morning we reflected

If one by one we counted people out

For the least sin, it wouldn't take us long

To get so we had no one left to live with.

For to be social is to be forgiving.

Our thief, the one who does our stealing from us,

We don't cut off from coming to church suppers,

But what we miss we go to him and ask for.

He promptly gives it back, that is if still

Uneaten, unworn out, or undisposed of.

It wouldn't do to be too hard on Brad

About his telescope. Beyond the age

Of being given one for Christmas gift,

He had to take the best way he knew how

To find himself in one. Well, all we said was

He took a strange thing to be roguish over.

Some sympathy was wasted on the house,

A good old-timer dating back along;

But a house isn't sentient; the house

Didn't feel anything. And if it did,

Why not regard it as a sacrifice,

And an old-fashioned sacrifice by fire,

Instead of a new-fashioned one at auction?

Out of a house and so out of a farm

At one stroke (of a match), Brad had to turn

To earn a living on the Concord railroad,

As under-ticket-agent at a station

Where his job, when he wasn't selling tickets,

Was setting out up track and down, not plants

As on a farm, but planets, evening stars

That varied in their hue from red to green.

He got a good glass for six hundred dollars.

His new job gave him leisure for stargazing.

Often he bid me come and have a look

Up the brass barrel, velvet black inside,

At a star quaking in the other end.

I recollect a night of broken clouds

And underfoot snow melted down to ice,

And melting further in the wind to mud.

Bradford and I had out the telescope.

We spread our two legs as it spread its three,

Pointed our thoughts the way we pointed it,

And standing at our leisure till the day broke,

Said some of the best things we ever said.

That telescope was christened the Star-Splitter,

Because it didn't do a thing but split

A star in two or three the way you split

A globule of quicksilver in your hand

With one stroke of your finger in the middle.

It's a star-splitter if there ever was one,

And ought to do some good if splitting stars

'Sa thing to be compared with splitting wood.

We've looked and looked, but after all where are we?

Do we know any better where we are,

And how it stands between the night tonight

And a man with a smoky lantern chimney?

How different from the way it ever stood?